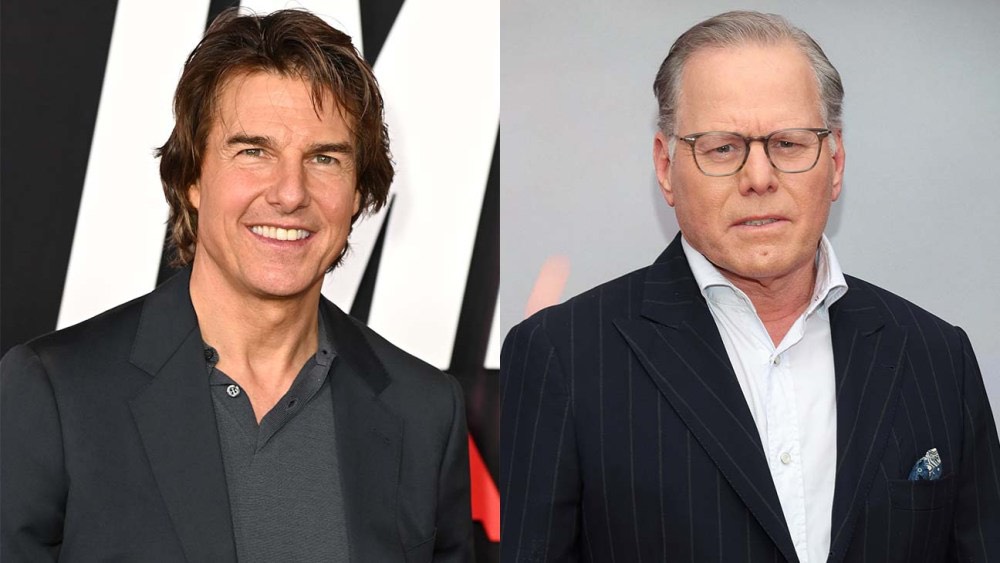

Last February, David Zaslav made his way to CAA’s offices, accompanied by his film-studio chiefs, Michael De Luca and Pam Abdy. The delegation gathered in agent Maha Dakhil’s office, where Kevin Huvane and Joel Lubin were in attendance. Also there was a prized client: Tom Cruise.

The meeting was the product of a call that De Luca and Abdy had made to Dakhil. They asked Dakhil to pass along a message of thanks to Cruise for working so hard to save theaters. The star was then still in the process of pulling the seventh Mission: Impossible movie together, which he had dragged against heavy odds through the pandemic. Meanwhile, Top Gun: Maverick had restored faith in the viability of movie theaters. Cruise would later promote Barbenheimer, a rare move for an actor who had nothing to do with either film.

The CAA meeting went on for two hours. Cruise is a true veteran when it comes to dealing with Hollywood executives, and he and Zaslav instantly clicked on the importance of keeping movies and theaters alive. By the time the meeting adjourned, it was clear that a deal was going to be done.

It’s notable that Paramount — then spending hundreds of millions on two Mission: Impossible installments — was never looped in on the discussion. Cruise doesn’t have any kind of formal deal at the studio, but he’s had a long relationship there through multiple executive regimes. Five of his past seven movies were for Paramount, but some of the bloom seems to be off that rose.

Sources say Cruise was not happy with the way Paramount dealt with him on a number of issues. He had lawyered up in 2021, when the studio announced that Top Gun: Maverick would have a mere 45-day theatrical run (which of course did not happen). The studio also pressed Cruise to approve the making of a television show based on Mission: Impossible or Days of Thunder for its streamer.

No doubt Cruise also knows that Paramount is a melting ice cube, a company very much in search of a deal, and he might think Warners would be a more secure home base. (While Cruise didn’t have offices on the Paramount lot, he plans to set up shop at Warners.)

Paramount has had some issues with Cruise, too: He and his writer-director, Christopher McQuarrie, have had a tendency to change their minds on the fly while filming, which tends to bust the budget. The release date for Mission: Impossible Dead Reckoning — Part One was pushed four times. Ultimately, sources say, the movie lost north of $25 million. (Some sources believe the loss was very far north of that.)

“Tensions have gotten higher between Tom and Paramount as relates to budget and collaboration,” says a source with knowledge of the situation. “He doesn’t send script pages, doesn’t let them see dailies. He used to be very responsible on budgets. That changed on Dead Reckoning.”

At 61, Cruise is still a big international movie star, one of the last of that species. “He’s probably got another 10 or 20 years, maybe not hanging off buildings, but as a movie star,” says an executive who has worked with the star. Cruise appears to think he can still hang off any building he chooses. Rather than returning to making films like Born on the Fourth of July or Lions for Lambs, studio sources say Cruise is intent on launching another big franchise. Sources say the Warner deal includes a greenlight on a yet-to-be-identified project, maybe a thriller or an action movie.

De Luca and Abdy have also hoped to lure Cruise back for a follow-up to the 2014 film Edge of Tomorrow, which the studio already had in development before they took over. (The well-reviewed picture, which cost $175 million, only grossed a disappointing $370.5 million but developed a cult fan base after its release. McQuarrie said in 2014 that Cruise had an idea for a prequel; director Doug Liman said it would be better than the original.)

Cruise’s new deal with Warners won’t produce anything starring Cruise anytime soon, given that the star will be working on the latest and possibly last Mission: Impossible until May 2025. And the deal doesn’t actually bind Cruise to do anything for the studio. “I’m not sure what [the Warners deal] is,” says a competitor. “It sounds like more of a David Zaslav headline than a movie.”

Zaslav has stepped on some rakes during his tenure in Hollywood, starting with the infamous dumping of Batgirl. But he has also dreamed of restoring Warner Bros. to its glory days, and told De Luca and Abdy when he hired them that he wanted to see the biggest stars and directors make a home on the studio lot. How that dream will work in terms of the Cruise deal remains to be seen: Zaslav has worked to slash the company’s heavy debt, while Cruise has a way of prying wallets open. “Good luck to them with Tom,” says an executive who has worked with the star.

But another veteran executive who has dealt with Cruise sees potential value to the deal even before it produces anything beyond an announcement. “Their ability to say, ‘This is the home of Tom Cruise’ — I think they perceive it as a coup,” this person says. “It never hurts to have a very close relationship with the biggest movie star in the world. It does provide cachet. It says, `This is a real place.’”