When archaeologists studying a fifth-century Swedish site found a human skeleton lying on the floor of a house, they wondered why no one had buried it. Then they found another. And another. All showed signs of having been executed with swords, axes, and clubs and then abandoned until the walls of their houses collapsed in on them. “It dawned on us that this was actually a massacre,” Clara Alfsdotter, a graduate student at Linnaeus University in Sweden and an archaeologist with the Bohusläns Museum, told the New York Times. They’ve found the remains of 26 people so far, along with a half-eaten fish (suggesting the attack was a surprise), coins, and jewelry, but they have not found any indication of who the attackers were or what they were mad about. Check out the ancient mysteries researchers still can’t explain.

A network of caves in Kenya called Panga ya Saidi holds human artifacts, from the Middle Stone Age straight through to modern times. Michael Petraglia, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, told Haaretz that with more than 1,000 square feet of space in its main chamber, the cave could have housed hundreds of people, and its tropical forest location has enjoyed a relatively steady climate while other parts of Africa have endured droughts. His team found large stone tools from the earliest inhabitants; more specialized arrowheads and blades started appearing around 67,000 years ago.

Hierakonpolis was one of the most significant towns along the Nile River 5,000 years ago (hundreds of years before the pyramids were constructed), and its wealthy residents showed their status by keeping exotic pets. A cemetery excavation has turned up two elephants, several baboons, and a hippo, among other animals. But it wasn’t all kibble and petting—skeletons of several of the baboons and the hippo showed signs of bone fractures that had healed; researchers think they got hurt during capture or while being tied in place. The bones would only have been able to heal while the animals were protected, though, which is how we know they were kept in captivity.

Hunter-gatherers buried several people, including two adolescent boys, at a site called Sunghir a couple of hours east of present-day Moscow 34,000 years ago. When the graves were excavated, researchers found that the boys—who died at roughly ages 10 and 12, and who both showed signs of disability—were buried together (heads adjacent) with 10,000 mammoth ivory beads, more than 20 armbands, around 300 pierced fox teeth, 16 ivory mammoth spears, carvings, antlers, and human fibulae laid across the chest of each child. Among the adults, on the other hand, some graves had no treasures, and others had only a few. Don’t miss these other 15 science mysteries researchers can’t solve.

More than 90 percent of modern humans descend from a small population of Homo sapiens that left Africa about 60,000 years ago, according to genetic evidence. Researchers think that group might have been so successful because they had developed superior stone tools—fine stone blades that could be used on the ends of spears, rather than bulky hand-axes. But a site in southern India, where ancient human sites have not been well-studied, shows that people there had advanced tools more than 200,000 years ago. Whether that means that human ancestors left Africa in waves or that different hominids came up with similar innovations separately is unknown, but intriguing. These mysterious ancient tools might intrigue you as well.

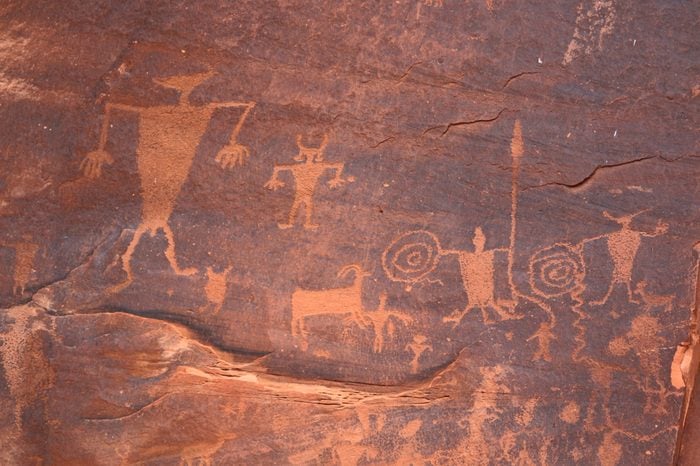

Just like his dad before him, Utah rancher Waldo Wilcox and his entire family kept mum about the ancient pit houses, prehistoric rock lines, paintings, and stone tools that were all over their 4,000-acre property called Range Creek. The artifacts had been left by a mysterious tribe called the Fremont Indians that lived in the area 1,000 years ago, and they remained mostly undisturbed, thanks to the Wilcox’s gates and “road closed” signs, erected to deter hunters. When Waldo decided he was too old to manage the ranch, he sold the property to the Bureau of Land Management and it’s now being overseen by the Utah Museum of Natural History. Here are some forbidden places no one will ever be allowed to visit.

When laborers digging a well in China in 1974 discovered a life-size statue of a soldier, they knew it was something special, but they had no idea what else lay below the surface. Archaeologists started excavating and currently think there are as many as 8,000 clay statues. Most are warriors, each with its own facial expression and weapons, and there are full-size terracotta horses and chariots too. The project was created as a mausoleum for the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang Di, who took the throne in 246 B.C. Qin is buried in a tomb at the site that hasn’t yet been excavated because of concerns about its stability, but explorations around the edge of it have uncovered statues of dancers and acrobats. Find out about the weirdest inventions ever.

In 2003, a six-inch-tall skeleton with a pointed head was found naturally mummified in the Atacama Desert of Chile. Although many people have claimed that the skeleton—which had bone density characteristic of a 6-year-old despite its tiny size—was an alien, scientists have since been able to sequence and study its DNA. Ata, as the female mummy is known, turns out to be a human being—she was most closely related to indigenous Chileans but also had some European ancestry. Researchers found seven different mutations of her genes that are involved with growth, but they’re not sure which caused her skeletal malformation.

A Greek ship sank off the coast of the island of Antikythera about 2,000 years ago and sat on the sea bottom until it was discovered in 1900. As archaeologists sorted out the artifacts that were retrieved from the wreck, they came across an object they didn’t know what to make of—it had multiple layers of brass gears precisely fitting together and built into a wooden box. A half-century later, a science historian figured out that it could predict the positions of the planets and stars in the sky by date. Since then, researchers have found Greek text on the artifact that showed it could also predict eclipses, moon phases, and a countdown to sporting events, including the Olympics. These accidental discoveries were put to good use.

Peruvian anthropologist Sonia Guillen was excavating a 1,000-year-old cemetery south of Lima, but her team didn’t find only humans: 43 dogs had been buried there by the people of the Chiribaya culture, which preceded the Inca Empire. The valued pets, which were used for herding llamas, had separate plots near their human owners, and many were buried with treats and blankets. Because the desert climate preserved the bodies of the dogs, Guillen could see how similar they looked to a popular modern breed called the Chiribaya shepherd, and her team is now trying to prove a genetic lineage. Some places on Earth are still unmapped.

About 1,300 years ago, a woman in the Italian town of Imola died just a couple of weeks before she was due to give birth. Archaeologists discovered the skeleton of her fetus between her legs, making her an example of a rarely observed “coffin birth”—gases build up inside the body of a pregnant woman and push the fetus through the birth canal. But scientists are more interested in another unusual finding: someone had created a small hole in the mother’s skull before she died. Drilling such a hole was called trepanation, and it has been performed throughout history and all over the world to treat head injuries, headaches, and possibly to get rid of evil spirits. In this case, researchers wonder if she was suffering from preeclampsia or eclampsia—pregnancy-related conditions involving very high blood pressure and possibly seizures. These mysteries were also easily explained by science.

More than 11,000 years ago, at the end of the Stone Age, hunter-gatherers remained nomadic; they had not yet settled down to the agricultural lifestyle which formed the basis of our cities and towns today. However, this archaeological site in Turkey has cast doubt on the timeline, because it has large pillars with animal carvings, stone rings, and loads of rectangular rooms. It might be the oldest known architecture in the world, and many researchers think it may be a religious complex. Find out the strangest unsolved mysteries of planet Earth.

Sometimes the weirdest artifacts turned up during a dig come from the archaeologists themselves. Peter Der Manuelian, a professor of Egyptology and director of the Harvard Semitic Museum, recalled via email that one of his Harvard predecessors, Dows Dunham, tried to fool his own boss, renowned Egyptologist George Reisner, who directed many of the most successful excavations of the pyramids. In 1914, Dunham tossed a bronze Roman coin he’d just bought at a Cairo antique shop into a burial chamber that was about to be excavated, to see whether Reisner would be confused. It didn’t work: As soon as the objects from the chamber were sorted out, Reisner knew his protégé had planted the coin. (Interestingly, Manuelian says that one of Reisner’s meter sticks was found in early 2018 in a tomb in Middle Egypt, 103 years after he first worked there.)

Sources: